What are mycotoxins?

Mycotoxins are natural substances produced by moulds.

All natural materials and many man-made ones are subject to contamination by moulds and under favourable environmental conditions, when temperature and moisture are conducive, these fungi proliferate and may produce mycotoxins. Over 500 mycotoxins have been identified and this number is steadily increasing.

See also: knowmycotoxins.com

The threat to ruminants

In comparison to monogastrics, ruminant animals are generally considered to be less susceptible to mycotoxicoses. This is based on the assumption that rumen flora degrade and inactivate in-feed mycotoxins. However, a number of mycotoxins resist rumen breakdown and ruminants often have to deal with a myriad of different challenges because their diet is complex. What’s more, transition cows are particularly sensitive to moulds, fungal spores and mycotoxins.

Did you know?

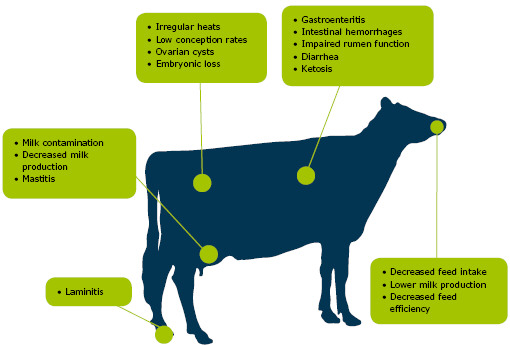

Mycotoxins in dairy cows can be a big issue. A healthy rumen has an ability to protect cattle against low levels of mycotoxins, but not all. Often these hidden thieves are likely to be responsible for numerous undiagnosed health issues.

In extreme cases they can cause abortion storms, severe scouring and sudden milk drop, but for the majority any mycotoxin presence is more likely to be seen as a subtle problem – perhaps the cows are not milking as well as they should be, or the dung is a little loose and variable, or cell counts have crept up and fertility is falling away.

The complex diet challenge

Ruminant diets typically contain both concentrates and forages. This increases the risk of exposure to multiple mycotoxins. Forages (grazed and conserved), fermented feeds and by-products all represent a significant risk to cattle depending on soil contamination, forage harvesting date, silage management, purchased feed origins and on-farm feed storage conditions.

Mycotoxins in Forages

Mycotoxins in forages (grass, hays, silages) present the greatest threat to cattle. Even fresh grass for grazing can be contaminated with several mycotoxins. These typically include fungal endophytes that produce mycotoxins, which protect the plant in some way, such as ergovaline and lolitrem B, as well as Fusarium mycotoxins, such as zearalenone or deoxynivalenol (DON).

Cattle are typically fed conserved forages (as silage) during the winter. Ensiled forages are more likely than dry forages (e.g. hay) to harbour moulds and associated mycotoxins – especially when fermentations and anaerobic conditions are not strictly controlled. Feeding any silage showing signs of mould growth should be avoided.

Identifying moulds in silage (Mahanna, 2009):

| Fungus | Mould colour | Associated toxin(s) |

| Penicillium | Green-blue | Ochratoxin, citrinin, patulin |

| Aspergillus | Yellow-green | Aflatoxin, ochratoxin |

| Fusarium | Pink-white | Zeralenone, DON, T-2, Fumonisin |

Mycotoxins in bedding

Straw bedding can be contaminated with mycotoxins. This also presents a risk to cattle, particularly for dry cows that often consume large quantities.

Types of Mycotoxins

Ochratoxin:

Ochratoxins are produced during storage of feedstuffs by different fungi and are found in both temperate and tropical regions. Ochratoxin A is the most prevalent. However, in a correctly functioning rumen this mycotoxin is rapidly degraded so is assumed to be a lesser threat to ruminants.

Clinical signs of Ochratoxin toxicity may include pulmonary oedema. Very high levels of Ochratoxin (e.g. 3ppm) can cause increased mortality.

Patulin:

Not considered to be a particularly potent mycotoxin, Patulin is produced by certain fungal species of Penicillium growing on fruit, including apples, pears and grapes. Fruit by-products stored under conditions that promote bruising and rotting increase the probability of Patulin formation. Contamination with Patulin has also been reported in vegetables, cereal grains and silage.

Clinical signs of Patulin toxicity in cattle include haemorrhaging in the digestive tract.

Aflatoxin:

What is Aflatoxin? Aflatoxins can occur in all regions across the globe as a result of factors such as changing weather patterns and agricultural practices, but are of greatest concern in more tropical regions where the climate is generally warm and humid. Be cautious though if feed is being imported from tropical regions.

Tricothecenes:

Tricothecenes [e.g. T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON or Vomitoxin)] are common field toxins found in grains and silages. These mycotoxins can be partially metabolised in the rumen, although their breakdown can be inhibited by acidic rumen conditions. Susceptibility to Tricothecenes vary between species, breeds and management systems. For example, beef cattle and sheep a more tolerant to DON consumption than dairy cattle.

Clinical signs of Tricothecene toxicity include reduced feed intake, lower weight gains and lost milk production, diarrhoea, reproductive failure and even mortality.

Zearalenone:

Zearalenone often occurs in combination with DON in naturally contaminated cereals or forages. This mycotoxin mimics the activity of hormones (as an oestrogen analogue), which causes the majority of the reproductive-related symptoms seen, especially in pregnant animals. Zearalenone is partially metabolised in the rumen to alpha-zearalenol and, to a lesser extent, to beta-zearalenol. These breakdown compounds have shown no toxic effects on rumen bacteria, but alpha-zearalenol is about four times more oestrogenic than its parent mycotoxin and so this rumen-mediated transformation actually causes greater toxicity. The rate of zearalenone transfer into milk is low and is currently through to present no real risk to consumers of dairy products.

Clinical signs of zearalenone toxicity include abortions, decreased embryo survival, infertility, vaginitis, feminisation of young males and mammary gland enlargement in virgin heifers.

Fumonisin:

Fumonisins occur worldwide in feedstuffs. In contrast to other mycotoxins, Fumonisin B1 (the most prevalent of the Fumonisins) is relatively slowly and poorly metabolised in the rumen. Ruminant target organs damaged by these mycotoxins include the liver and kidney.

Clinical signs of Fumonisin toxicity include reduced feed intake, lower weight gain and lost milk production.