The concepts of ruminant nutrition

The objective of this introduction is to provide more of an understanding of how we can produce rations which will not only satisfy the animals needs but also produce the best performance at the most efficient cost structure.

Fortunately, there is now a whole range of books and computer software available, which contain lists, tables and equations telling us how much of each nutrient we will need, to feed the particular animal we are trying to ration. So, we don’t have to worry about calculating much of the information that we need.

Having said that, it helps to gain a better understanding of the diet if we know the basics of how the rations are quantified

Modern rationing is much more about knowing how to make sense of the computer-generated gobbledygook that is often put in front of us, than actually having to work it all out. No, it is probably wise to get hold of a decent piece of software to do the spade work and learn how to interpret the result.

The bad news is that to do this effectively, it is vital that there is a good understanding of what makes a good ration and equally, what makes a bad one. This means that we still need to have a good grasp of the principles involved in ruminant nutrition.

When considering the animals needs, the first thing to think about is “What is the food going to be used for?” It really is, a very simple question, but the answer provides all sorts of clues as to how to construct the diet needed.

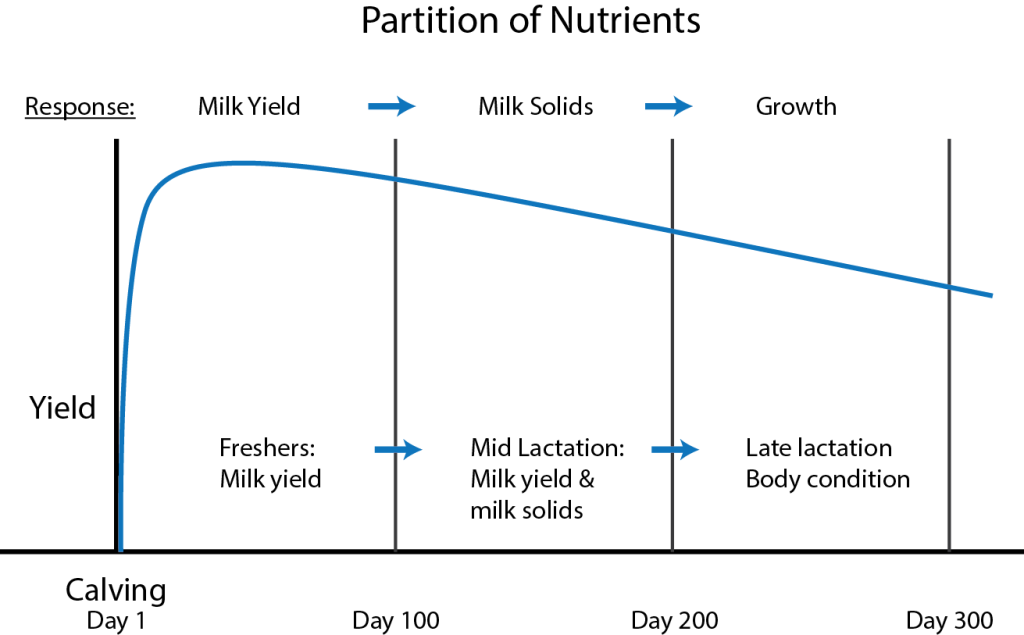

Scientists refer to this question as “The partition of nutrients”. All this really means is, what does the animal do with its food?

All animals need food to maintain their body systems. Maintenance requirements are the nutrients that the animal needs just to keep itself running healthily and includes the energy needed to move about and keep warm. Maintenance requirements are met before anything else can happen. The animal also uses food for growth (including laying down fat or condition), producing milk and pregnancy.

These four factors are of fundamental importance and must be considered individually when constructing rations. For example, it might sound obvious, but it is no good building a list of requirements for a lactating cow if we forget to add in the nutrients that she needs for growth in her late lactation. This is particularly important for heifers and ewes finishing their first lactation.

Nutrient requirements are normally broken down into the following key elements: –

| • Dry Matter Intake | (DMI) |

| • Metabolisable Energy | (ME, MPE) |

| • Protein | (CP, MPE, ERDP/MPN, DUDP/MPB) |

| • Minerals & Vitamins | |

| • Water |

These nutrient sources are normally sub divided into individual nutrient components.

For example, individual key minerals like calcium, phosphorous, magnesium; or energy sources like starch, sugar and NDF etc, etc.

The animal’s requirements for each nutrient varies according to its level of production.

The most efficient way of feeding the animal is to supply it with exactly the right amount of each nutrient. This is unrealistic, so what happens in practice is that we supply the key nutrients like energy and protein as exactly as possible and then we try to get a “best fit” of all the others.

The use of powerful computer models has made the whole process a lot more effective than it used to be, because the computer can simultaneously calculate all the nutrients required in the diet and strive find the best mix from the feed materials available.

The main pitfall with the computer is usually the operator! I frequently see examples of computer-generated diets that have been out-dated by changes in the forages or the herd calving pattern; or they relied on inaccurate feed analysis or inappropriate production information. These diets tend to be way off the mark as far as accuracy is concerned and as a result tend to be expensive.

It is generally agreed that the best practise is to reassess the feeding regimes of all the livestock groups at least once a month. Most of the time there will be no real changes bar a tweak here of there, but sometimes the diet needs to be completely reformulated.

There is also a need to get the boots dirty and go and have a look at what the cows are telling us. The “Cow Signals” system is really an intuitive look at a great stockmanship ideal.

Checking the muck, sorting, rumen fill, hock hygiene, udder condition, cudding rate, cubicle lying, etc etc: can tell us a lot about how well the diet is working but also highlights many other stock management issues.

Transition cow scoring has been shown to be an invaluable tool in predicting performance in the ensuing lactation of dairy cows. Nothing like this exists for sheep but any objective assessment of the close-up ewe would generally be a useful tool for predictive management.

Feed into Milk (FiM)

In 2002 a new model for rationing dairy cows was introduced.

Feed into Milk (FiM) represents 12 years of development from the Metabolisable Protein system (MP model) widely adopted in 1990.

There were changes in most of the prediction equations and there is also a better appreciation of rumen fermentation patterns. As a result, we now have some new terms to think about.

In order to fully understand FiM I have decided to explain the old MP model terms since they form the foundation of the new rationing techniques.

I have concluded each section with a description of the relevant FiM model terms. This will make it a lot easier for the reader to get to grips with the language and thinking behind FiM.

Many nutritionists subsequently reverted to a hybridised development of the old MP model because FiM seems to have some limitations with both high and low yielding cows and we finished up using fudge factors just like we always did!

Writing in 2020, much of the current modelling has moved forward from even ten years ago, current models look at nitrogen use efficiency, predict methane output, predict water consumption, look at the first limiting amino acids and rumen buffering.

None of this was available when Feed into Milk was first released.

I have no doubt that the models will continue to develop but it is difficult to escape from the fact that nutrition probably accounts for about 20% of the key factors that can affect animal performance.

Anyone who owns a dog will know that environment, routine, and exercise are fundamental factors that determine the performance and well being of the animal. Equally the old adage “The more you put in the more you get out” is also true.

The attention to detail that I have witnessed in the management of the best herds of cows, beef enterprises and flocks of sheep, is proof positive that management and stockmanship also need to go hand in hand with good nutrition.

For the record, my Ultramix (2020) program allows me to select from four updated models MP, FiM, the French PDI and the new NutriOpt system (NutriOpt after 1st November 2020). This allows for a better approach to prediction, but we still need to get our boots dirty!